An iPhone keyboard for blind users will be discontinued, according to the app's developer, who alleges that "Apple has thrown us obstacle after obstacle for years while we try to provide an app to improve people's lives."

FlickType includes an Apple Watch keyboard and the iPhone keyboard intended for blind and low-vision users of VoiceOver, an Apple technology that can speak the key a user selects. FlickType's Apple Watch keyboard will continue, at least for a while, but the iPhone keyboard will be disabled.

"It's with a heavy heart today that we're announcing the discontinuation of our award-winning iPhone keyboard for blind users," the FlickType account on Twitter wrote yesterday. FlickType is developed by Kosta Eleftheriou, who recently filed a lawsuit alleging that Apple used its control over iPhone app distribution to induce him to sell FlickType to Apple at a discount. He says he refused to sell the app.

Apple “incorrectly” rejected app update

The last straw for FlickType's keyboard extension came last week when Eleftheriou "submitted an update that fixes various iOS 15-related issues & improves the app for VoiceOver users," FlickType wrote. "But Apple rejected it. They incorrectly argue again that our keyboard extension doesn't work without 'full access,' something they rejected us for THREE years ago. Back then we successfully appealed and overturned their decision, and this hadn't been a problem since. Until now."

FlickType said it contacted Apple nine times last week "with no success. At this point they seem to be ignoring our attempts to contact them directly, despite previously explicitly telling us to 'feel free' to contact them if we need 'further clarification.'"

The app's keyboard extension will stop working after future updates. "We wish to keep providing the last working version that includes the keyboard extension, but Apple makes it impossible to stop automatic updates for individual apps. So unless you stop automatic updates for all your apps, you will soon lose the FlickType keyboard extension," FlickType wrote.

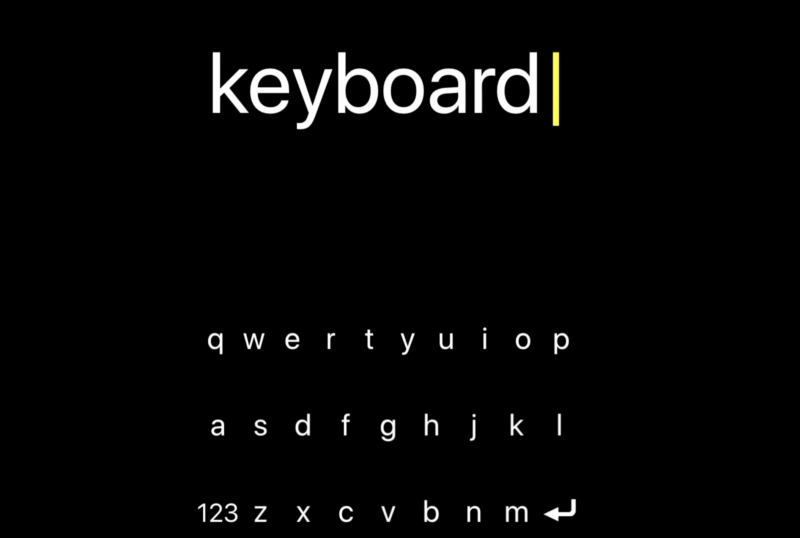

The app's App Store listing says, "FlickType keyboard is designed to be as accessible as possible on both iPhone and Apple Watch, featuring large keys, high-contrast colors, prominent visuals, and effective VoiceOver feedback. FlickType can speak back to you for a completely eyes-free writing experience, enabling people who are blind to type just as fast as everyone else."

The American Foundation for the Blind's AccessWorld publication wrote an article in October 2018 about how FlickType solves an annoying problem for blind users. "When I first began to use a smartphone, I found that the most cumbersome aspect was the touchscreen keyboard," AccessWorld Editor-in-Chief Aaron Preece wrote. "Finding the correct key is fairly simple, but the delay as you wait to hear the name of the focused key adds a surprising amount of time to the act of typing." Preece found that "FlickType is much more fluid to use than the default keyboard" and that when "FlickType predicts what I have typed correctly, I find it increases the speed of my typing around 30 percent or so."

A National Federation of the Blind article called FlickType "a much faster experience than the standard iOS keyboard."

Keyboard works without full access

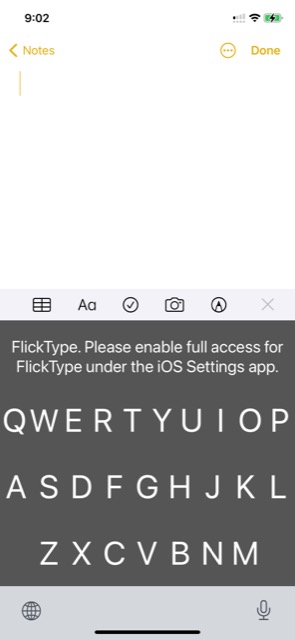

Apple rejected the app update on August 13, sending Eleftheriou a note that says, "We noticed that your keyboard extension does not function when the 'Full Access' setting is toggled off. To resolve this issue, please revise your app to ensure that your keyboard extension is fully functional with or without full network access."

Eleftheriou showed Ars the message from Apple, which contained a screenshot of the FlickType keyboard that asks users to "please enable full access for FlickType under the iOS Settings app."

Without full access, "FlickType supports regular touch typing where you explore the keyboard and then lift your finger to enter the desired character," a support page says. Enabling full access unlocks "tap typing," in which blind and low-vision users can "lightly tap where you think each letter is, and FlickType's powerful algorithm will correctly guess the right word almost every time."

Tap typing "allows users who are blind to not have to wait for feedback for each key, effectively allowing them to type as fast as anyone," Eleftheriou told us. He pointed out that other keyboards, such as the Microsoft-owned SwiftKey, also ask for full access to enable extra capabilities.

"Requiring full access for certain additional features is nothing new," he told Ars.

Apple's App Store reviewers don't seem to realize that the iPhone keyboard works without full access as long as VoiceOver is enabled, Eleftheriou told The Verge. "They'd have to try it as a VoiceOver user, something that they don't seem to bother doing. I've had several rejections in the past because the reviewer didn't know anything about VoiceOver," he said.

Eleftheriou says Apple must stop “developer abuse”

When asked if he'd continue providing the iPhone keyboard if Apple reverses the update rejection, Eleftheriou told Ars that "Apple would need to do more than just reverse their decision. I've already gone to great lengths over the years to personally convince them to reverse dozens of their wrong decisions in the past. They'd need to at least admit that they've been treating me and thousands (millions?) of other developers unfairly and unreasonably for years. Admitting this would be the first step towards them actually reducing, and eventually stopping, this developer abuse."

Eleftheriou said he isn't sure how long he'll keep developing the Apple Watch portion of the app. "I'm still going to try to provide the watch keyboard, for now at least," he told Ars.

Developers' complaints about the Apple App Store have resonated with some lawmakers, as Congress is considering legislation that would force Apple to let users sideload apps and access third-party app stores.

We contacted Apple today and will update this article if the company answers our questions.

Eleftheriou’s lawsuit against Apple

This is not the first public dispute between FlickType's developer and Apple. Eleftheriou calls himself a "professional App Store critic" and has worked to identify scam apps that trick users into making payments that might otherwise go to legitimate apps.

Eleftheriou's California-based company, Kpaw, sued Apple in March, alleging that the iPhone maker "threw up roadblock after roadblock" to make it difficult to get FlickType onto the App Store.

Apple was trying to buy FlickType from Eleftheriou and evidently "thought plaintiff would simply give up and sell its application to Apple at a discount," the lawsuit alleged. The complaint, which was filed in the state superior court in Santa Clara County, continued:

Once plaintiff finally got its application to market, plaintiff's application vaulted to the top of the App Store's sales worldwide. Then, copycat and scam applications surfaced, driving down plaintiff's sales. What's worse, these scammers vaulted to the top of sales in the App Store by submitting fake reviews to elevate themselves in Apple's system. Plaintiff complained to Apple and, in response, Apple did next to nothing, despite its stated policies forbidding this precise type of unfair competition. While Apple enticed plaintiff to develop and publish applications for sale in the App Store based on Apple's promise of a "safe" environment, Apple does not in fact police its App Store, undoubtedly because it profits massively from rampant developer misconduct and consumer fraud. By this lawsuit, plaintiff seeks to recover its losses as result of, and bring to an end to, Apple's fraudulent and unfair practices.

Last week's app-update rejection "is the tip of the iceberg," Eleftheriou told Ars. "The big picture is the years-long pattern of rejections as well as the extremely poor 3rd-party keyboard APIs."

reader comments

176